The New Oil (Part 3): Can Technology End the Rare Earth Dependency?

By Cygnus | 14 Jan 2026

For the last two decades, the world has treated rare earths like a geological problem: find more deposits, open more mines, build more supply. But after the 2026 supply shocks and policy tightening exposed the fragility of critical mineral dependencies, the real question has shifted.

It is no longer “How much can we mine?”

It is “Can technology make us need less?”

This is where the story becomes more complicated—and more hopeful. There are two major technology pathways now being positioned as escape routes from rare-earth dependence:

- Magnet recycling (recover what we’ve already mined)

- Rare-earth-free motors (reduce demand in the first place)

Both ideas are real. Both are accelerating.

But neither is a silver bullet—at least not on the timelines markets are pricing in.

The hard truth: dependency lives in magnets, not just mines

Rare earth elements are not mainly a “battery minerals” story. They are a magnet story.

Permanent magnets—especially NdFeB (neodymium-iron-boron)—are foundational to:

- EV traction motors

- wind turbine generators

- robotics and industrial automation

- advanced defence systems

And magnets are difficult because once rare earths are transformed into magnet-grade material, the supply chain becomes less about extraction and more about processing know-how, precision metallurgy, and manufacturing infrastructure.

In other words, this is not just about physical scarcity. It is about capability scarcity.

1) Magnet recycling: the “urban mine” that finally makes sense

For years, magnet recycling sounded like a circular economy slogan. In 2026, it is turning into an industrial strategy.

The concept is simple:

Recover rare earths from existing magnets already embedded in end-of-life products.

But execution is hard, because magnets are often:

- sealed inside motors

- blended into multi-material assemblies

- spread across dispersed consumer products

- contaminated with coatings, adhesives, and alloys

The breakthrough is not chemistry — it’s collection

The biggest constraint is not whether rare earths can be recovered. It is whether magnets can be reliably collected at scale.

Recycling becomes viable when there is:

- standardized “design for disassembly”

- high volumes of retired EV motors / turbines

- predictable scrap streams

- a stable recycling price floor

IEA analysis has emphasized that recycling can reduce pressure on primary supply, but scaling requires targeted policy and industry infrastructure.

The magnet-to-magnet dream

The most strategic version of recycling isn’t just recovering rare earth oxide. It is “magnet-to-magnet” recovery—restoring material directly back into usable magnet production with minimal loss.

That is the prize:

recycling that doesn’t rebuild the same dependency on refining.

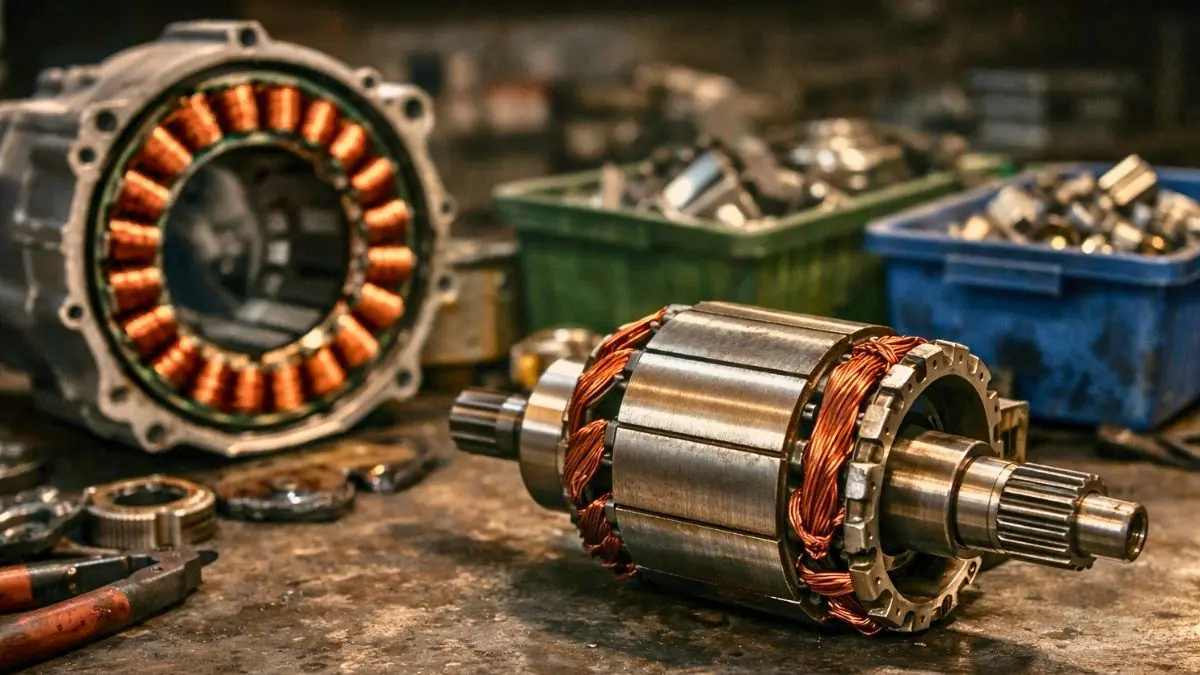

2) Rare-earth-free motors: the engineering war under the hood

If magnet recycling is about recovering supply, rare-earth-free motors are about weakening demand.

Today, the industry reality is blunt:

Most EV motors still depend on rare earth magnets.

S&P Global Mobility has noted that motors requiring rare-earth elements dominate the e-motor market today, but alternative designs are gradually gaining share as supply risk becomes a boardroom issue.

What rare-earth-free actually means

There are several engineering routes:

A) Induction motors

- no permanent magnets

- mature and proven

- strong performance, but efficiency trade-offs at certain operating points

B) Switched reluctance motors

- robust design

- no rare-earth magnets

- but needs high-end control electronics to manage noise, torque ripple, and refinement

C) Synchronous reluctance motors

- high efficiency in some configurations

- magnet-free versions possible

- trade-offs on torque density and drivability

Academic and industrial literature increasingly highlights switched reluctance motors as a serious alternative pathway.

The trade-off no one likes to say aloud

Rare-earth magnets didn’t win because of marketing. They won because they are:

- compact

- efficient

- high torque density

- easier to package into modern EV architectures

Replacing them is possible—but it takes compromises:

- more copper and steel

- higher complexity in software and controllers

- redesign of supply chains

- sometimes heavier motors for same output

So the transition is not a flip. It is a gradual migration.

Timeline realism vs hype: what changes by 2026–2030

This is where investors get trapped.

Markets want a clean story:

“Technology will solve the rare earth problem.”

Reality is messier:

What improves fast (2026–2028)

- pilot recycling capacity expands

- early rare-earth-free platforms appear in select models

- governments fund R&D and standards

OEMs diversify motor architecture to reduce risk

What improves slowly (2028–2035)

- large-scale magnet collection networks

- stable recycled feedstock quality

- mass adoption of magnet-free motors

- magnet manufacturing outside China at scale

This is why the dependency doesn’t “end.”

It fractures—and becomes less absolute.

The strategic bottom line: dependency will shrink — but not disappear

The most important insight isn’t whether the world becomes rare-earth-free.

It is this:

Technology can reduce the strategic leverage of rare earth chokepoints.

Magnet recycling + motor diversification don’t eliminate dependence in 2026 or even 2030.

But they can:

- reduce the shock impact of export restrictions

- stabilize OEM planning

- weaken monopoly pricing power

- shift bargaining power across regions

That is not a clean decoupling.

It is a rebalancing.

Summary

Part 4 of The New Oil series explores whether technology can reduce global dependence on rare earth supply chains. Two key pathways—magnet recycling and rare-earth-free electric motors—are accelerating as governments and manufacturers respond to supply risks. Recycling could unlock a scalable “urban mine,” but requires collection systems, standards, and industrial capacity. Magnet-free motors (including induction and reluctance designs) offer real alternatives, but still involve trade-offs in cost, packaging and performance. The net result is not an overnight break from dependence, but a gradual weakening of the rare-earth chokepoint over the next decade.

Also Read (The New Oil Series):

- Part 1: Rare Earths — The First Shock

- Part 2: Lithium & Graphite — The EV Bottleneck

- Part 3: Inside the Processing Gap

- Part 4: Can Technology Break the Dependency?

- Part 5: Friend-Shoring, Supply Chain Fragmentation and the Cost of Resilience

Frequently asked questions (FAQs)

Q1: Can recycling eliminate rare earth shortages?

Not entirely. Recycling can meaningfully expand secondary supply over time, but it requires large-scale collection, consistent scrap streams, and industrial processing capacity.

Q2: Why are rare earth magnets so hard to replace?

Because permanent magnets provide high torque density and efficiency in compact form factors—ideal for EVs, robotics and wind turbines.

Q3: Are rare-earth-free EV motors already available?

Yes. Induction and reluctance motor designs already exist and are being developed further, but they are not yet the dominant industry standard.

Q4: When will technology meaningfully reduce dependency?

Progress is expected through 2026–2030, but large-scale structural change will likely take most of the decade as supply chains and production platforms evolve.

Q5: Does this mean China’s dominance disappears?

No. But it may reduce the severity of supply shocks and weaken monopoly leverage if recycling and alternative motor architectures scale globally.