JILA Scientists use electric felds to control chemical reactions of ultra cold molecules

03 May 2010

As described in the April 29 issue of Nature (K K Ni, S. Ospelkaus, D. Wang, G. Quéméner, B. Neyenhuis, M.H.G. de Miranda, J.L. Bohn, J. Ye, and D.S. Jin. Dipolar collisions of polar molecules in the quantum regime) JILA scientists discovered that applying a small electric field spurs a dramatic increase in chemical reactions in their gas of ultracold molecules. JILA is a joint institute of the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) and the University of Colorado at Boulder.

|

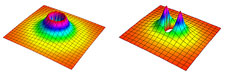

| Schematic depiction of an energy barrier between polar molecules in an ultracold gas. The fully symmetrical barrier (left) arises only between molecules known as fermions, which if identical cannot occupy the same place at the same time. This barrier greatly reduces the likelihood of chemical reactions. When an electric field is applied to the gas, the barrier is modified (right) so its height varies by direction. Molecules that approach each other parallel to the electric field face a lower barrier and are more likely to react. If molecules approach each other perpendicular to the electric field, then the barrier is raised. |

The discovery builds on the same JILA research team's recent pioneering observation of how molecules behave in the chilly world near absolute zero, which is governed by the curious rules of submicroscopic quantum physics. In this realm, the molecules act like waves instead of particles, and overlap of the waves determines whether chemical reactions occur to create different molecules.

In their experiments, researchers study chemical reactions between pairs of ultra-cold molecules, each consisting of a single potassium (K) atom and a single rubidium (Rb) atom. These KRb molecules are susceptible to electric fields because they are electrically "polar": they have a positive electrical charge at the rubidium end of the molecule and a negative charge at the potassium end.

In this latest publication, the researchers measured how electrical fields can control the rate at which these KRb molecules react, discovering how to speed up the reactions or slow them down. Controlling reactions in this way can allow researchers to create molecular products tailored for practical applications.

"We want these molecules to survive for a long time in our trap so that we can go on to do other quantum physics experiments, such as quantum simulations and quantum information processing," explains NIST Fellow Jun Ye, a senior author of the new paper.