New structures self-assemble in synchronised dance

26 Nov 2012

With self-assembly guiding the steps and synchronisation providing the rhythm, a new class of materials forms dynamic, moving structures in an intricate dance.

|

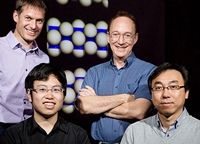

| Researchers from the University of Illinois and Northwestern demonstrate tiny spheres that synchronize their movements as they self-assemble into a spinning microtube. From left, Erik Luijten, Jing Yan, Steve Granick and Sung Chul Bae. Photo by Brian Stauffer |

Researchers from Northwestern University and the University of Illinois have demonstrated tiny spheres that synchronise their movements as they self-assemble into a spinning microtube. Such in-motion structures, a blending of mathematics and materials science, could open a new class of technologies with applications in medicine, chemistry and engineering.

''The world's concept of self-assembly has been to think of static structures -- something you would see in a still image,'' said Steve Granick, founder professor of engineering at the University of Illinois and a co-leader of the study. ''We want shape-shifting structures. Structures where a photograph doesn't tell you what matters. It's like the difference between a photograph and a movie.''

The researchers used tiny particles called Janus spheres, named after the Roman god with two faces, which Granick's group developed and previously demonstrated for self-assembly of static structures. In this study, one half of each sphere is coated with a magnetic metal. When dispersed in solution and exposed to a rotating magnetic field, each sphere spins in a gyroscopic motion. They spin at the same frequency but all face a different direction, like a group of dancers in a ballroom dancing to the same beat but performing their own steps.

As two particles approach one another, they synchronize their motions and begin spinning around a shared centre, facing opposite directions, similar to the way a couple dancing together falls in step looking at one another.

''They are both magnetised, which causes them to attract each other, but because they're moving, they have to move in sync,'' said Erik Luijten, a professor of materials science and engineering and of applied mathematics at Northwestern's McCormick School of Engineering and Applied Science. He co-led the research with Granick.