Fast molecular rearrangements hold key to plastic's toughness

29 November 2008

The stiff-but-malleable quality of plastics that allows them to bend rather than break when put under stress, attracts new research findings. By Jill Sakai, University of Wisconsin-Madison

Plastics are everywhere in our modern world, largely due to properties that render the materials tough and durable, but lightweight and easily workable. One of their most useful qualities, however - the ability to bend rather than break when put under stress - is also one of the most puzzling.

|

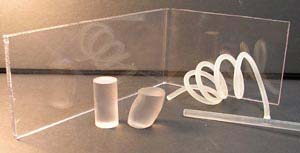

| Polycarbonate, a type of polymer glass, can be bent (sheet), mashed (cylinder), or twisted (rod) without breaking. Photo: Hau-Nan Lee |

"This is an odd combination of properties... These materials shouldn't be able to flow because they're rigid solids, but some of them can," he says. "How does that happen?"

Ediger's research team, led by graduate student Hau-Nan Lee, has now described a fundamental mechanism underlying this stiff-but-malleable quality. In a study appearing 28 November in Science Express, they report that subjecting a common plastic to physical stress - which causes the plastic to flow - also dramatically increases the motion of the material's constituent molecules, with molecular rearrangements occurring up to 1,000 times faster than without the stress.

These fast rearrangements are likely critical for allowing the material to adapt to different conditions without immediately cracking.

Plastics are a type of material known to chemists and engineers as polymer glasses. Unlike a crystal, in which molecules are locked together in a perfectly ordered array, a glass is molecularly jumbled, with its constituent chemical building blocks trapped in whatever helter-skelter arrangement they fell into as the material cooled and solidified.