|

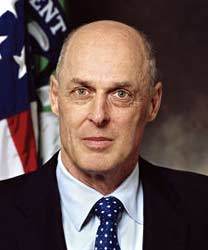

A modified version of the Paulson bailout plan has been approved by the US Congress, though the changes are merely cosmetic and even amusing. Now that it is a done deal, will it work? By Shivshanker Verma  Finally, the US Congress has backed treasury secretary Henry Paulson's modified plan to save the world. As many as 32 Democrats and 26 Republicans, who voted against the plan earlier this week, changed their minds and the bill was passed with a comfortable margin. The US Senate had approved the bill in between and president Bush wasted no time in signing off the deal. Finally, the US Congress has backed treasury secretary Henry Paulson's modified plan to save the world. As many as 32 Democrats and 26 Republicans, who voted against the plan earlier this week, changed their minds and the bill was passed with a comfortable margin. The US Senate had approved the bill in between and president Bush wasted no time in signing off the deal.

By the close of business on Friday, Paulson's plan was law and he can now spend $250 billion immediately to buy distressed mortgage securities. The treasury department can ask for the rest of the $700 billion in instalments, depending on how fast he can spend the first instalment, how successful the plan is perceived to be and how convincing Paulson's successor will be before the US Congress. So, what changes were made to the plan to convince the 58 members of the US Congress in a matter of four days? The most obvious change is the bailout plan document became a lot more bulky. Paulson's original plan was just three pages. The plan, when first defeated by the US Congress, was nearly 200 pages as the politicians added lots of bells and whistles to protect themselves from criticism and to create the impression that they were indeed in control. The modified and approved plan was stretched to 451 pages before the US Senate stamped its approval, that persuaded the House of Representatives to do likewise. In substance, nothing much has changed. The treasury will have almost unlimited discretionary powers to price and buy distressed mortgage securities, or any other type of securities - including even car loans and student loans - which it considers important. Treasury can buy from any institution of its choice, through a process of its own design, which is as yet unknown and at a pace which the treasury deems appropriate. The provisions regarding the acquisition of equity or senior debt in participating institutions in return for government support and executive compensation remain vague. It is not clear if the government will insist on acquiring majority stakes in participating institutions, changes in top management or business restructuring. The addition most talked about is the increase in deposit insurance from $100,000 to $250,000 per depositor, per bank. On the face of it, this looks appropriate and should help reassure retail depositors that their savings held in bank deposits are safe to that extent. When everyone is scared about the integrity of the financial system, a measure to improve the confidence of retail depositors can do no harm. Or, so it seems. But, how does that help to solve the crisis? It will not improve the value of distressed securities held by banks or help the banks to raise additional capital. It will not encourage banks to lend to each other, the biggest problem in this crisis, as long as they remain fearful of each other's health. All that this increase in deposit insurance will do is to possibly prevent large scale runs on bank deposits, in case the crisis worsens. But, if that actually happens, the US government will be in more trouble than it is now. Deposit insurance is offered by a government-controlled agency, in return for a fee collected from all banks accepting deposits. The fee now collected from banks is barely enough to cover $100,000 for each depositor. If some banks actually fail and the government agency is forced to pay up $250,000 per depositor, per bank, the government will end up footing the bill. Another clause in the approved bill grants the market regulator, the Securities and Exchanges Commission, discretion to relax the fair value accounting rules, more commonly known as mark-to-market accounting. These rules require the values of securities to be adjusted to current market rates, every quarter, irrespective of whether such securities are intended to be held till maturity. Much of the losses reported by the big banks in recent quarters are because of this provision. When the market value of the illiquid mortgage-backed securities declined, every bank which held those securities was forced to write down its asset values and reported huge losses. It is true that mark-to-market accounting rules accentuate the losses when there is a market crisis, because the prices quoted in the market during such phases of extreme stress can be grossly distorted. But, that was precisely one of the reasons for introducing such rules in the first place. These rules were also intended to encourage banks and other institutional investors to keep their hands off illiquid and risky investments, the prices of which are prone to wild fluctuations. The assumption was that the fear of big losses in mark-to-market asset write-downs would force banks to stick to safer securities which are traded in well developed and liquid markets. It is true that mark-to-market rules have not served this intended purpose. But, that was not because the rule itself is flawed but because banks became complacent and never imagined that it can hurt so much. Even if the rule is assumed, for a moment, to be flawed, the only alternative is to accept asset valuations by 'experts' for all illiquid assets. The many crises and scandals of the past have laid bare the risks of relying too much on 'expert valuations' which can be highly subjective, biased or even manipulated. In effect, what the US lawmakers are suggesting seems to be to allow firms the discretion to value assets at market prices when it is good for them and rely on expert or even internal valuation when that is more favourable. Such selective adoption of rules and wide discretion to firms can lead to even more troubles in future. In the midst of heated debates, US lawmakers didn't forget to squeeze in completely unrelated tax and spending provisions to benefit their constituents. The plan which was originally proposed to bailout financial institutions now contains offers of tax breaks for research and investments in clean energy, small businesses suffering from the economic downturn and even individuals. Hilarious it may seem, but the bill also includes an excise duty waiver for 'wooden arrows' and an expansion of some healthcare plans to include mental illness. Maybe the lawmakers found the last provision a necessary addition in these highly stressed times! Of course, these were added on the pretext of making the bailout more palatable to ordinary Americans. In the end it was just one factor which forced many lawmakers to support the bailout, public opinion. When the Paulson plan was first introduced, popular perception was that it was simply a scheme to bailout the culprits of the current financial crisis at a huge cost to the taxpayer. This encouraged many Congressmen, many of them seeking re-election, to vote against the plan the first time. When the stock market tanked and the credit crisis seemed to have worsened after the initial rejection of the original Paulson plan, public mood changed perceptibly as the adverse effects of the credit crisis on ordinary people became more apparent. The dithering US lawmakers sensed this sudden shift in public mood and merely adjusted their positions accordingly. Now that the bailout plan is a done deal, the only question that remains is whether it will work? With all its flaws, the Paulson bailout plan is a risky venture. Given the ambiguities built into the plan, the whole scheme is vulnerable to scandals on securities pricing, management of assets bought under the plan and their eventual disposal. At the mere whiff of any scandal, the same lawmakers who now supported the deal will race to pull it down. That makes the management of this bailout a political minefield, left to the next administration with a new treasury secretary. Henry Paulson has already started appointing key personnel for administering the plan and is also reported to have started the search for asset managers. The treasury now seems to be inclined to outsource most of the bailout administration to private entities and limit its own role to supervision. Accordingly, it is believed that up to 10 private asset managers will be appointed to manage the assets purchased under the plan. Big names like PIMCO, Black Rock and Legg Mason are said to be in the reckoning for what will be some of the world's biggest asset management accounts. Heavy private sector involvement, that too from the same community of investment bankers who are perceived to be the villains in this crisis, will make political management of the plan all the more difficult. In the short term, the most important development to look out for is the psychological effect the bailout plan will have on the financial markets. If credit flows ease and equity markets stop falling, the bailout would have achieved its first objective of calming the markets. In normal times the markets might have even recovered on their own, once calmness returns. But now, the US economy seems to be slipping rapidly into a recession and is pulling down global growth as well. Nobody knows for sure what other assets now held by banks and other institutional investors will next face erosion in value. Also, if the contagion spreads to all parts of the world as it seems to be happening now, potential sources of capital for the world economy - like the oil exporting countries - will dry up. The US government, powerful as it may be, will find it difficult to expand the scope of the bailouts as the already highly strained fiscal situation will now allow that. Hopefully, it will not come to that. That is the prayer of all the good folks who now support the Paulson plan, despite its shortcomings. Because it is the only plan available at this moment, every one has to live with it.

|