|

Iranians love to eat, and the greatest pleasures of gluttony are so abundant in Iran —notwithstanding the post-revolutionary disappearance of sherry, wine, and ham from recipes. In fact, no cookbook can capture the pleasures of taste we used to so easily take for granted in Iran. Iranians love to eat, and the greatest pleasures of gluttony are so abundant in Iran —notwithstanding the post-revolutionary disappearance of sherry, wine, and ham from recipes. In fact, no cookbook can capture the pleasures of taste we used to so easily take for granted in Iran.

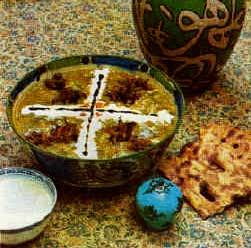

Iranian restaurants in Mumbai cannot be compared to their counterparts in Iran where the only options are kebabs and rice. I wonder what vegetarians would do. My favourite is kabab-e-jujeh, chicken marinated in just lime and curds and barbecued. Insist on the chicken being barbecued till the skin becomes golden-brown and crisp. At Zoroastrian pezerishgahs (rest houses) and homes, one may savour the traditional zerest pulao, or berry pulao with fried chicken and rice delicately perfumed with herbs like mint, saffron, cinnamon, dill, berries, orange peels, cherries and nuts, or osh, a traditional speciality prepared with lentils cooked with noodles and flavoured with dill. The aerated, salted buttermilk was fun. Lunch in a restaurant comprises fresh greens accompanying a mountain of rice topped with a huge dollop of butter and the rarest of meat kebabs I had laid my eyes on with minimal, if any, seasoning. I was clueless about how this could be relished. I asked, then for a chilly, but comprehension dawned only after I handed the waiter a sketch. Iranian food habits are not as elaborate as the Indian. They use dry lemons, tomato paste, garlic and a bit of spice in some of their curries called khoresht. Otherwise, they consume kababs or fried chicken with rice, the inevitable greens and the bowl of fresh garlic curd. Fish is generally served only in the better restaurants in large city centres or along the Caspian coast. The chello mohi — fish fillet crumb—fried to accompany steamed rice, potato chips and tomatoes without dal or patio to go with it is an interesting variation. Along the Caspian coast, the fish will be the world-famous sturgeon from which caviar is derived. If you are lucky, you may be served khoresht (daily gravy) or else it will be just flavoured rice and fried fish.  The local nunvah (baker) who supplies your daily quota of hot chapattis off the oven, in varieties called nune sangek, nune rogani, nune lavash, nune barberry etc, (flatbread varieties baked in a tandoor, a cylindrical clay oven on which flattened dough gets cooked over a hot charcoal fire) every morning and evening, saves you the trouble of preparing them at home. For breakfast, Iranians have nun with eggs, cream, honey or sausages, teamed with a couple of cups of black tea (chai). They keep themselves busy munching nuts and dry fruits most of the time and drink innumerable cups of chai through the day. I remember how my search for biryani (Indian flavoured rice dish containing meat, fish, or vegetables) turned out to be one of the greatest anticlimaxes of all time. I was as thrilled to know that biryani was available, as they were to know that Indians liked biryani. We sat down at this roadside stall famous for biryani. After some time, they brought us something akin to minced meat parathas known as beryani. We then realised that in Persian bery means roasted, grilled meat. The torshe or pickle comprised of salted vegetables, and the only ones I liked were the salted baby cucumbers, that with mayonnaise, made a good breakfast on toast. The falooda served in Iran is nothing like the one you find in Bombay or Poona at Badshah's. It's more like the Sindhi falooda available at Kailash Parbat. Each province has a speciality of its own. Faloodehye shirazi is a rose water drink (shorbet) that contains small pieces of cooked rice noodles. The dish is subtle, slightly sweet with just a hint of rose petals; the noodles add chewiness and a little flavour. Faloodeh is served with a wedge of lemon, which adds a refreshing kick. It is an ideal way to end a meal on a searing hot day. You can order Faloodehye shirazi in Ice-cream shops and most teahouses (chai khaneh). Having tea or faloodeh in the teahouses of the world famous gardens of Shiraz is recommended. Consuming alcoholic drinks is forbidden in Iran. However, every kind of alcohol that foreigners need is available through the Armenian community. If ever you plan a trip to Iran, do not miss the umpteen fruit varieties. Most of these fruits do not really have names in English, only approximations, which make them mysterious markers for nostalgia. The three fruits of paradise, quince, persimmon, and pomegranate are unforgettable. Some say that pomegranate, the symbol of fertility and love, originated in Iran and was taken to the West during the wars between the Persians and the Greeks. The Greeks coveted the fruit to such an extent that it came to be known as Aphrodite's fruit, thrown recklessly to the recipients of her love and grace. What cookbook could write of the crunchy bitter kiss of choghaleh badam or unripe almonds? Fresh walnuts in salt water, the brown skin peeling back, is my favourite. The walnut flirts with you, offering its fragrant white flesh, sinuous folds on the surface like the pleats of a maiden’s gown. Even cucumber tastes so much more intensely delicious than anywhere else in the world. Every house has a samovar, which keeps water boiling through the day, and hot water required for chai (tea) is available at any time. Even serving chai is ritualistic. The cherry red coloured chai is served in tiny glass cups along with dates or sugar cubes. Chai is always served after a meal; you have to sip the chai through sugar cubes held between your teeth. I wonder how the sugar cube lasts so long for them; for me, it simply melts in a minute. We went to one of the traditional teahouses, (sofrekhaneh sonnati) where we had some more chai, and ate dates and other fruits, whose names I did not know. We were offered the qalyun, or water pipe. That really was a great experience. They put fruit tobacco in the bottom, cover it with aluminium paper, and place a piece of red-hot coal on top of it. A brass pipe connects to the water in a bowl and the smoke is drawn through the water to the mouthpiece. In the winter, we celebrate with boiled sugar beets sold out of carts on the corner of the street. You peel back the harsh, darkened skin with your thumb, and underneath, the luscious scarlet flesh of the beet invites you to bite into it, steam in the frozen air, and there is rarely a taste as intensely sweet. Iranian writers have penned many an ode to sugar beets in the winter. Read more on tantalizing Tehran

|