|

A distinguished Indian defence scientist now says that the yield of the H-bomb device in the country's 1998 ''Buddha Smiles'' nuclear tests was much below expectations and that the test was a 'fizzle,' raising concerns about the potency of the country's nuclear arsenal. A look at the controversy, and what it portends, by Rajiv Singh. New Delhi: Reviving a controversy that had erupted in 1998, almost immediately after Pokhran-II ''Buddha Smiles'' nuclear tests, a distinguished Indian defence scientist now says that the tests may actually not have been the success they were said to be in one particular respect. According to K Santhanam, the yield of the thermonuclear device was actually much below expectations and the test was a 'fizzle.'  | Key scientists and engineers on 10 May 1998.

Abdul Kalam is on left (silver hair);

R. Chidambaram is holding file;

Anil Kakodkar is behind Chidambaram wearing glasses; K. Santhanam is at extreme right. | In nuclear parlance, a test is described as a 'fizzle' when it fails to deliver the desired yield. There would perhaps be nothing new about the controversy, as India's claims that the tests had indeed met the benchmarks set for them was hotly contested within a few days of the tests itself by foreign governments and monitoring agencies, which pointed out discrepancies between the Indian claims and the seismic 'readings' of their monitoring machines. The thermonuclear (Hydrogen bomb) test was said to have yielded 45 kilotons (KT) but the claim was challenged by Western experts who said it was not more than 20-25 KT. Santhanam, who was director for 1998 test site preparations, apparently made the admission, at a semi-public seminar on the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty at the Institute of Defence Studies and Analyses (IDSA) on Tuesday. The seminar followed the Chatham House Rule, under which the identity of the speaker is not revealed, though what he or she said is freely quoted. Santhanam apparently stressed at the seminar that India needed to conduct more tests to improve its nuclear weapons programme. "There is no country in the world," he emphasised, "which managed to get its thermonuclear weapon right in just one test."  | | Preparing to fire the devices in the control bunker, code named "Deer Park." K. Santhanam transfers the firing keys to the range safety officer Vasudev. | Yesterday he told a daily, ''Based upon the seismic measurements and expert opinion from world over, it is clear that the yield in the thermonuclear device test was much lower than what was claimed. I think it is well documented and that is why I assert that India should not rush into signing the CTBT.'' All this directly contradicts government claims that India has all the data required from such explosions and can now manage with computer simulations. It is also the first confession from one of the original Pokharan-II scientists that the thermonuclear test had not quite worked out to the extent that the Indian government would have liked. Cat amongst the pigeons

Howsoever hard the government may try to deny, it is a given that the Indo-US nuclear treaty is predicated on India not testing nuclear weapons again. This was the point around which the whole domestic debate had revolved. If Santhanam avows that the country, for the sake of a robust and credible nuclear deterrence, needs to test again then the carefully crafted structure of the Indo-US nuclear treaty begins to come apart at the seams. Experts at home are already beginning to hail Santhanam's "extremely courageous stand," even as former president Dr APJ Abdul Kalam has stepped in to clarify that the tests were successful and had generated the desired yield. "After the test, there was a detailed review, based on the two experimental results: (i) seismic measurement close to the site and around and (ii) radioactive measurement of the material after post shot drill in the test site," Kalam said. "From these data, it has been established by the project team that the design yield of the thermo-nuclear test has been obtained," said Kalam, who as director general of the Defence Research and Development Organisation, spearheaded the nuclear tests in 1998. But then, in 1998, even as Dr Kalam was declaring success, then Department of Atomic Energy chief, R Chidambaram claimed that they had deliberately kept the secondary stage of the thermonuclear Shakti- I explosion low so as not to damage a nearby village. This was his way of trying to explain away the low yields from the first of the two tests, which foreign sources were claiming was not commensurate with the test of a successful thermonuclear weapon design. There were also other explanations. Shakti-1

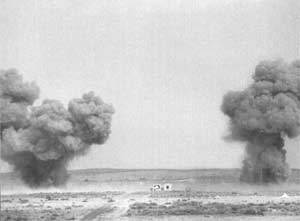

| | Nuclear bomb (probably the Shakti I thermonuclear device) being lowered into test shaft. | The May 1998 'Buddha Smiles' tests involved six designs of varying yields. The tests were organized into two groups that were fired separately on two separate days. The first group consisted of a thermonuclear device, a fission bomb and a sub-kiloton device. The second group consisted of two more sub-kiloton devices. The first group of explosions were dubbed Shakti I-III and the second group, with two explosions, Shakti IV-V. A third design Shakti VI was never exploded. What is causing the controversy is the yield from Shakti-1, the thermonuclear device, or the hydrogen bomb, which was also the largest device tested. A thermonuclear device operates in two stages. First a normal plutonium implosion device (primary) acts as a trigger to set off a fusion or thermonuclear process (secondary) that releases a vast amount of energy. Shakti I was a two-stage thermonuclear design, using a boosted fission primary, which DAE chief R Chidambaram claimed had a yield of 43kt (also described as 43kt +/- 3kt). Western sources claimed that the yield was in the range of 22-25kt. They also pointed out that a plain reading of the Indian government's own seismic evidence puts the yield at, or below, 25kt. This was, of course, disputed by BARC scientists (including Dr Anil Kakodkar, who was part of the team) who published a series of papers showing through radio- chemical analysis that the yields were as expected.  | | Dust columns from the Shakti test series on 11 May 1998 | The doyen of Indian nuclear scientists, PK Iyengar, former chairman of the Atomic Energy Commission and one of the original group who worked on the Indian nuclear weapons programme almost from inception, and was involved in the 1974 nuclear test, had this to offer Reuters on 12 May, a day after the tests. Iyengar spoke about the differing sizes of the Shakti I-III series and how they corresponded to three differing weapon designs. The first group of explosions, as has been pointed out, consisted of a thermonuclear device, a fission bomb and a sub-kiloton device. According to Iyengar, the smallest (sub-kiloton) was the size that could be used as an artillery fired shell, or dropped from a combat support aircraft. The mid-size, fission bomb was from a standard fission device equivalent to about 12 kilotons -- the size that might be dropped from a bomber plane. The largest of the three warheads tested on that day, he said, was not a full hydrogen bomb. Most of its explosive force came from the primary, a fission device which serves as a trigger for the H-bomb's big fusion explosion. According to Iyengar, the device contained only a token amount of the hydrogen variant tritium. It showed, he said, that India's thermonuclear technology worked, but did not produce the megaton explosion typical of a full H-bomb. "We need not go for a megaton explosion while testing an H-bomb," said Iyengar. "Such tests are required only if we are planning for a total destruction of the opposite side. They don't have relevance in our strategy." But then there are explanations and explanations and the fact remains that there is an ambiguity around the May 1998 tests that remains unresolved to this day. A scientist of the seniority and stature of Santhanam is not given to shooting off his mouth unnecessarily. If Santhanam's claim is correct, then no responsible Indian prime minister can agree to signing the CTBT even as its own nuclear arsenal suffers from defects in design and technology. Fancy rollouts of nuclear powered submarines can only be an object of derision for powers who need to be impressed with our deterrence capabilities. An unequivocal statement on the issue, either by scientists or bureaucrats, would be too much to expect, given the sensitive nature of the subject matter. Now for a look at why the controversy may have reared up again after eleven years. Engaging Washington

Though the controversy is old hat for security experts and analysts, Santhanam's revelation now sets the cat amongst the pigeons in the policy-making spheres of the government (read the PMO). The controversy couldn't have come at a worse time for the UPA government's somewhat beleaguered prime minister Dr Manmohan Singh, who not only contemplates a widespread drought situation in the country but has also just finished wiping off a lot of egg from his face - post the NAM summit at Sharm-el-Shaikh. The Indian prime minster is now all set to depart for Washington, where a newly installed Obama administration will receive him as its first foreign guest - a unique honour. What awaits him there may not be very difficult to guess. Post-Sharm-el-Sheikh, secretary of state, Hillary Clinton, found herself fending off accusations that it was under US pressure that India made the kind of concessions it had to Pakistan.

Brushing off such accusations in an interaction with the press, she tried to put a positive spin on the relationship reiterating the Obama administration's commitment to the Indo-US civil nuclear agreement. However, she said, on her forthcoming trip to India she would like to discuss with Indian leaders the ways to prevent the "proliferation of nuclear material and weapons to state and non-state actors that pose a threat to India, to the US, and to the many countries around the world." This was a polite way of saying that NPT/CTBT linked issues were back on the table, and also a message that the Democratic Party had returned to the evangelical mode of operations in foreign affairs, setting aside a more laissez faire approach of Republican administrations. Clinton redux

The Obama administration has made its non-proliferation agenda amply clear, not just through policy statements, but more importantly in the recruitment of a large number of people to positions of influence in its administration who are ex-non-proliferation zealots of some sort or the other. The appointment of the new ambassador to India, Timothy Roemer, is only one example of non-proliferation 'experts' occupying positions of influence in the administration. Given the mass recruitment of ex-members and policy wonks from the Bill Clinton administration to staff positions in the new administration, we need to remember that the Clinton administration, amongst all the wars that it engaged in with a Republican-controlled House and Senate, was also involved in a bruising, and unsuccessful, war with the Republicans on the issue of ratifying the CTBT. This apart from a much-publicised, and a very unsuccessful, attempt to push through a Hillary Clinton-promoted health care plan. No surprises, but both agendas are now back on top of the table with the new Democratic administration. After eight years of a Republican presidency, the only existing recruitment pool that the Obama administration can now tap to man its offices and policy making positions is from the Clinton administration. A lot of baggage, ideological and otherwise, will travel with them. Obama has promised on the international stage that he would get the CTBT ratified at home and, along with Russia, make 'deep' cuts to the country's nuclear arsenal. In this task he would appear to have an easier job on his hands than Clinton, given his majority in both Houses of the legislature. Obama stepped into Washington with a lot of 'moral' authority with calls for 'Change.' As the recession wears on and he gets embroiled deeper in pushing his health care plan through the Congress and the Senate, he also sees his approval ratings slipping by the day from their dramatic highs. A chastened Republican Party, still nursing its wounds from the drubbing it has received in recent polls, is not likely to offer any easy victories to him, if it can help it. The CTBT never made any sense to them, and it is a matter of record that every Republican president has dumped the issue on assuming power. It is also a matter of record that every Democrat president has put it high on his agenda. Obama still needs 67 votes in the Senate, for ratification requires two-thirds majority, and at best he has 60. Even less if the vacuum caused by the passing away of Senator Ted Kennedy is not filled quickly enough. As he gets bogged down in Health Care reforms the Republicans may seize the chance and deny him any traction over CTBT-related issues as well, a treaty which they distrust almost as heartily as the Democrats seem to embrace it. It is up to the Indian prime minister to make of the situation what he will. He will be aware that the Indo-US nuclear deal was the only significant achievement that the Bush presidency could boast of. The deal was also achieved in the face of cut-throat opposition - not just here in India, but also in the United States. Once the treaty was done with, both countries went on to conduct elections from which a significant difference has emerged – the Indian opposition was completely sidelined by the parliamentary elections, whereas in the United States the opposition has moved into power. Non-proliferation is a significant component of the ideological baggage of the Democratic Party and its proponents had watched with horror as the Indo-US nuclear deal progressed to maturity. It is now baying for blood. This report may appear trifling, but is an indication of the language of the new Obama administration. On 19 August this year secretary of state Hillary Clinton swore-in her close ally, former Rep Ellen Tauscher, as undersecretary of State for arms control and international security. We quote verbatim from a published report: "The fact that secretary Clinton personally swore-in the new undersecretary is a testament to the very close relationship between these two veteran female politicians, a connection that goes beyond any formal bureaucratic lines of authority," a non-proliferation hand in attendance said. It's also "a reflection of the personal importance secretary Clinton places on the broad issues of arms control and non-proliferation. Indeed, for all the recent musings over where Hillary Clinton can make her mark in this administration, forging progress on strengthening the global non-proliferation regime and securing Senate ratification of such key agreements like the START follow-on treaty and the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty can lay the foundation for a very strong [Clinton] legacy." Amen! Of tests and CTBTs Here are some statistics that we may look at for our reading pleasure: From 1945 until 2008, there have been over 2,000 nuclear tests conducted worldwide. Between 1945 and 1992, when the United States of America stopped nuclear testing, it has conducted 1,054 atmospheric and underground nuclear tests. The Soviet Union conducted 715 nuclear tests between 1949 and 1990. Compare this with the six explosions conducted by India, spread over three days, since the first one in 1974. The 1998 tests have been declared adequate by Indian authorities, so the question arises what have the Americans been trying to achieve with their 1,000-plus nuclear tests? This is not even taking into consideration hundred of tests undertaken by the UK, France, China etc. Why are such huge numbers of tests required? Does it say something for Indian genius, or is there another, worrying, story that emerges from these statistics? As for the CTBT, of the total of 181 States that have signed the treaty only 148 have also ratified it. Amongst the nuclear weapons-states only three nations have done so - the Russian Federation, France and the United Kingdom. The notable absentees are the United States of America and China. To enter into force, the CTBT must be signed and ratified by 44 specific States. These are States that participated in the negotiations of the Treaty in 1996 and possessed nuclear power or research reactors at the time. Only thirty-five of these States have ratified the treaty. Of the nine remaining States, China, Egypt, Indonesia, Iran, Israel and the United States have signed the treaty but not ratified it. The Democratic People's Republic of Korea, India and Pakistan are yet to sign it.

|